1An important date in the morphodynamic history of Mauritania’s Atlantic coast is the arrival of the post-glacial sea at, or in the vicinity of its current level. This event took place between 6000 and 5000 years B.P. During the millennia that followed, the sea level varied very little, whereas the coastal area underwent considerable changes, marked by the formation of large deltas and lagoons, and more generally, a regularisation of the coastline through the reworking of sediment tracts.

2The factors involved in this redistribution include hypothetical sea-level variations, local or regional crustal movements, and the reworking of sediment stocks by coastal processes. Each of these factors is subject to natural and anthropogenic forcings. The purpose of this article is to establish a hierarchy of factors involved in the evolution of a site situated on the Banc d’Arguin coast in West Africa.

3The coast of Mauritania is lined by sandy beaches or mud and sand tidal flats. Rocky areas are located in the north of the country around Lévrier Bay, (fig. 1) and also appear as rare promontories that form capes (‘Ras’) along the shores of the Banc d’Arguin (Barusseau, 1985), vast shallow (<20 m) marine expanse covering some 7500 km2 (150 km from north to south; 100 km from east to west). Mahé (1985) describes this area as a lagoon-marine system, the legacy of an ‘undoubtedly deltaic past’ shaped by numerous channels and shoals. The boundary areas testify to this complex evolution. The Ras el Sass - Jerf el Oustani - Îmgoutene area (fig. 1) was formerly the site of an estuarine bay where the Oued ech Chibka, now completely dried up, reached the sea. A similar situation is observed in the neighbouring Oued el Atoui, already described by Chudeau (1921).

Fig. 1 – Location map of the study area

Fig. 1 – Situation de la région étudiée

A: R.I Mauritania in West Africa; B: Banc d'Arguin area in NW Mauritania; C: Estuarine bay of Oued ech Chibka; D: Study area

A: R.I. de Mauritanie en Afrique de l’Ouest; B: le secteur du banc d’Arguin en R.I.M.; C: la baie estuarienne de l’Oued ech Chibka; D: secteur étudié.

4Flat, low topographies (under 10 m) appear on the boundaries and inside the former estuarine bays, now filled by thick tracts of sand. Three main landscape units can be identified, namely boundary reliefs in the north, isolated massifs on the sandy plain (Jerf el Oustani, Jerf Sgheir) and peninsulas (Ras el Sass). These landscapes bear witness to a Quaternary formation, initially considered part of the region’s Quaternary marine record, the Tafaritian (Hébrard, 1973, 1978; Elouard, 1975), but since shown to be a continental, alluvial lakeside or sebkha formation, of an undetermined age (Giresse et al., 1989). A part of these Tafaritian reliefs formed islands when the continental shelf in this area was transgressed during the mid-Holocene.

5The observed tide is semi-diurnal and microtidal, with a range between 0.8 and 2 m (Mahé, 1985; Koopmann et al., 1979). The relatively flat bathymetry of Banc d’Arguin exposes considerable coastal flats at low tide, where the intertidal area can reach 600 km2 (Mahé, 1985).

6The swell is attenuated by Cap Blanc and the shallow bathymetry of the Banc. The dominant longshore drift runs south as shown by the numerous south-trending sand spits in this area (Barusseau, 1985). The spits also show the existence of a sedimentary conveyor fed in particular by the discharge of barkhan lines that trend SSW. Aeolian processes account for the onshore movement of these sandy masses, several metres in height and several dozen metres in length and width. These sandy masses feed on the imposing dunes formed during the period of base-level rise (post-glacial transgression) in the continental domain (Deynoux et al., 1991).

7A particular characteristic of the Banc d’Arguin coastal region is the presence of Neolithic shell middens. These have yielded abundant archaeological material consisting of pottery fragments and small tools, as well as remains of Anadara senilis, the main mollusc exploited by ancient human populations living in the Gulf. These middens and their archaeological content have been described in several studies (Amblard et al., 1990; Barusseau et al., 1995; Vernet, 1998; Descamps and Vernet, 2001; Vernet et al., 2001; Vernet and Ould Mohamed Naffé, 2003; Vernet and Tous, 2004; Vernet et al., 2004). The Neolithic populations exploiting A. senilis drew the resource from proximal tidal flats and subaerial coastal areas, where they could cook the heavy shells to extract the flesh. Owing to these two aspects of their work, ancient populations were geographically tied to the area’s seaboard.

8Other locations of coastal features are indicated in the Jerf el Oustani - Ras el Sass region by two sets of concentric lines (fig. 2), one that straddles the north cliff of Jerf el Oustani, the other joining the eastern cliff of Ras el Sass.

Fig. 2 – The two sets of nested berms (IGN–AOF 100, 1954)

Fig. 2 – Les deux ensembles de bermes emboîtées (d’après photo IGN–AOF 100, 1954).

9Our research methodology has been aimed at tying up the archaeological data with the sedimentological findings.

10In the study area, 143 shell middens were located using GPS (fig. 3) and their archaeological content rapidly analysed by visual observation and description of superficial remains. Four of the middens were fully excavated down to the Tafaritian substratum. The successive shell layers were removed by scraping 5 cm thick layers over the entire excavation area (2 x 1.5 m). A sample of the elements contained in each layer was sieved using a 2 cm mesh, yielding a suite of material including shells for radiocarbon dating, decorated fragments, microlithic quartz tools and various remains of organisms, in particular fish vertebra and otoliths. At one of the sites, a copper awl was recovered.

Fig. 3 – Location of the investigated and excavated shell-middens.

Fig. 3 – Position des amas coquilliers identifiés et fouillés

(Tafaritian outcrops denoted in grey)

(affleurements tafaritiens en gris).

11The archaeological remains can be used as dating elements in the well known context of the Mauritanian Neolithic (Vernet, 1998; Vernet and Ould Mohamed Naffé, 2003). Three large groups of evidence have been identified (fig. 4). The oldest remains belong to a period prior to 5000 B.P and are far less abundant than fragments from the following millennium. The latter belong to the “Tasiast ensemble” which is widespread in the region, in particular the Tintan culture, dated at ca. 4500-4300 B.P. Human presence is finally documented up to about 2600 years B.P. by a third group, represented by pottery shards and copper elements. A clear distinction can be drawn between older groups that had not mastered copper metallurgy, and more recent ones that had. This pattern was confirmed by 14C datings we undertook during the study.

Fig. 4 – Chronological data based on pottery shard typology.

Fig. 4 – Chronologie archéologique fondée sur la typologie des tessons.

12The geomorphology of coastal features identified on aerial photographs (fig. 2) was studied in the field. The surfaces in the study area are extremely flat but, in the field, numerous active barkhans prevent an overall view of the topography. On the large expanses of the former estuarine bay, it is also very difficult to gauge the precise topography of the very low slopes. A topographic profile of more than 4 km was therefore carried out using a total station, so as to establish an altimetric benchmark for sandy surfaces and locate palaeo-shorelines relative to mean sea level. At the same time, the tidal range was measured during spring tide by plotting the low and high tide levels. Contrary to the monospecific anthropogenic accumulations, an examination of the fauna contained in the natural deposits shows various shallow marine species in life position. Shell samples recovered in these sediments were 14C dated.

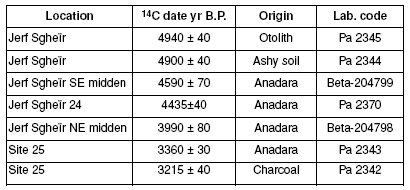

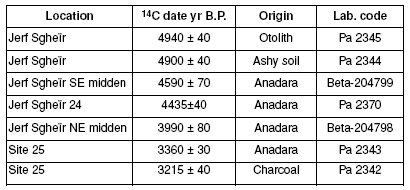

13A first observation stems from the precise positioning of the middens using GPS. They are generally arranged along lines linked to the progradation of the estuarine bay. We hypothesize that each midden broadly retraces the position of the coastline at each phase of occupation. The shell middens studied were grouped according to Vernet and Ould Mohamed Naffé (2003). The dating results (tab. 1) have confirmed these attributions while more precisely constraining details of the human occupation of the coastal boundaries.

Table 1 – Shell midden radiocarbon dates.

Tableau 1 – Datations au 14C d’éléments des amas coquilliers.

14Thus, the site of Jerf Sgheïr (fig. 1) testifies to an early occupation of a relatively remote point of the Tafaritian elevation occupied around 5000 years B.P. The high position of this small plateau rendered it particularly attractive for human occupation. Below the eastern side of Jerf Sgheïr, two small middens in the south and the north show Tintan culture archaeology. The radiocarbon dates, between 4500 and 4000 years B.P. confirm this chronology.

15The pattern of human occupation (fig. 5) shows that, prior to 5000 years B.P., no middens were formed in the estuarine bay; they were all situated on the edge of the Tafaritian steep slopes or on the dunes. An initial incursion in the bay occurred around 4900 years B.P., shown by the midden at Jerf Sgheïr, rich in fish debris (vertebra and otoliths), and its position making it possible to exploit coastal habitats. The remains of the Tintan culture are more widely distributed after this time. Accretion of the isthmus made it possible to reach Jerf Sgheïr after 4900 years BP. The sediment deposits were formed in the direction of the Jerf el Oustani plateau, separating the estuarine bay in its eastern part. The estuary was still connected to Oued ech Chibka and a marine bay to the west, largely open to the sea, in spite of the shielding role afforded by Cape el Sass. This pattern became more pronounced in both parts, which remained separated until ca. 3200-3300 years B.P. with numerous indications of a recent Neolithic occupation (fig. 5). After this, the trend was to build middens in the south and south-west of the eastern bay and in the western bay. These occupy positions that coincide in part with the locations of the palaeo-shorelines (cf. infra). The end of human occupation, ca. 2700-2600 years B.P., marked by the copper awl at site 25, does not indicate a greater extension of alluvial deposits and related shoreline forms. This extension can only be based on the morphology of landforms.

Fig. 5 – Location of shell-midden alignments on sand spit or beach ridges, showing human occupation of successive palaeoshorelines.

Fig. 5 – Situation des alignements d'amas coquilliers sur les flèches et cordons littoraux, montrant les occupations successives des paléorivages.

1: No 14C ages; ages older than 5000 years B.P. according to archaeology; 2: Jerf Sgheïr shell midden, 4900 years B.P.; 3: Tintan group, 4600-4000 years B.P.; 4: Last Neolithic groups, 3300 years B.P.; 5: Copper Age groups, 2700-2600 years B.P.; 6: unknown ages, no shards, no dates.

1: absences de dates 14C; plus ancien que 5 000 ans BP d'après l'archéologie; 2: amas coquillier de Jerf Sgheïr, 4 900 ans BP; 3: groupe « Tintan », 4 600-4 000 ans BP; 4: derniers groupes du Néolithique, 3 300 ans BP; 5: groupes de l'âge du cuivre, 2 700-2 600 ans BP; 6: âges inconnus, ni tessons, ni datations.

1614C dating was carried out at Jerf Sgheïr and site 25 (tab. 1), using Anadara shells and charcoal. The values are very close (3360 and 3215 yrs B.P.), without any notable reservoir effect.

17The general layout of the Tafaritian reliefs delineates an open palaeo-bay in which a number of islands played an important role in the morphodynamic evolution of the sedimentary filling.

18Observations in the field have shown that the palaeo-shorelines interpreted on aerial photos were actually berm accumulations forming ridges some 20 to 30 cm high and twenty metres wide, and trending eastwards. These sand accumulations define the progradation of palaeoshorelines, corresponding to the beach berm. They are accompanied by various marine fossils indicating a coastal origin (molluscs, crabs, fish or turtle bones, etc.). They are found in the form of dozens of nested shorelines that join Jerf el Oustani and a long arched bar (excavation site 25), in a west-to-east direction, and resting on the south-east boundary of the plateau. This morphology resembles a tombolo that joins the former island of Jerf el Oustani to the continent. For the more recent palaeoshorelines studied, vegetal debris is also observed, lining low high-water marks, and likewise delineating a tombolo at Ras el Sass.

19These different lines have formed on a sandy plain and are organised in concentric arcs, the general altitude of which is moderate (less than 1 metre above mean sea level). The overall topography of the estuarine bay (including beach berms) therefore lies in the tidal range based on present sea level (fig. 6), apart from a low beach ridge along the present shore and the current high barkhans not represented on the profile. As in the case of the berms, the fauna is characteristic of beaches and shallow coastal bottoms. Abundance and homogeneous spatial distribution indicate that the shells are in situ and not reworked.

Fig. 6 – Cross-shore topographic profile showing the entire sand flat within the current tidal range.

Fig. 6 – Profil topographique transversal totalement inscrit dans le marnage actuel.

HTSL/LTSL: high-tide and low-tide sea level.

HTSL/LTSL: niveaux de haute mer et de basse mer, respectivement.

Table 2 – Radiocarbon dating of the palaeo-berms.

Tableau 2 – Datations au 14C de coquilles des paléobermes.

20The dating of berm shell material attests to relatively young ages (tab. 2). After this time, Neolithic populations deserted the region because of deterioration in living conditions. Occupation of site 25 by the last Chalcolithic populations is contemporary with the beginning of berm construction, which is at the origin of the final infilling of Jerf el Oustani bay.

21The data and observations, as well as the chronological framework provided by the archaeology and radiocarbon dates, make it possible to reconstruct the morphodynamic evolution of Jerf el Oustani’s estuarine bay and the human occupation of its shores during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic.

22From a morphodynamic point of view, the layout of the bay’s Tafaritian shores and the pre-existing insular massifs restricted any subsequent evolution after the Holocene transgression. The regional oceanographic context can be presumed to have been established during this period, with a regime of dominant swell from the west or the north-west; under such conditions, various inevitable consequences ensued (fig. 7). First, easterly coastal drift developed on the north coast of Îmgoutene, completed by the formation of sedimentary spits where the rock promontory changed orientation. Subsequently, swell refraction and diffraction around the islands generated wave shadows that were conducive to the formation of tombolos.

Fig. 7 – Oblique view of proposed palaeo-hydro/morphodynamic processes in the former Oued ech Chibka bay.

Fig. 7 – Vue oblique montrant le schéma proposé des processus hydro- et morphodynamiques en action dans l’ancienne baie estuarienne de l’Oued ech Chibka.

1: dominant wave regime; 2: northern longshore drift active during the beginning of the period; 3 and 4: refracted wave fronts and associated orthogonals; 5 a and b: successive tombolos formed in the wave shadow of the islands; 6: Oued ech Chibka sediment input.

1: houles dominantes; 2: action de la dérive littorale en début de période; 3 et 4: réfraction des fronts de houles et orthogonales associées; 5 a et b: tombolos successifs formés à l’abri des îles; 6: direction des apports de l’Oued ech Chibka)

23These phenomena occurred under contexts of high sediment supply. It appears that the fluvial inputs of Oued ech Chibka and the dune sands (Deynoux et al., 1991) supplied significant sediment volumes to the coastal zone.

Fig. 8 – Successive stages in the construction of the sand flat.

Fig. 8 – Étapes successives de la formation du sand flat.

1: development of the spit joining Jerf Sgheïr; 2 and 3: beginning of the Oued ech Chibka infilling; 4: formation of the Jerf el Oustani tombolo; 5: rapid filling of the northern and southern bays either side of Jerf el Oustani tombolo; 6: formation of the Ras el Sass tombolo and sand flat completion.

1: développement de la flèche sédimentaire rejoignant Jerf Sgheïr; 2 et 3: début du colmatage; 4: formation du tombolo de Jerf el Oustani; 5: régularisation rapide des baies au nord et au sud; 6: formation du tombolo de Ras el Sass et régularisation du trait de côte.

24The geomorphology evolved in six phases (fig. 8), beginning with an early occupation phase of the high shores, prior to 5000 years B.P.

251. Under the action of the W-E coastal drift on the shores of Îmgoutene, the sediments transported to the east were blocked by the northern cliff. A spit developed, which rapidly joined the neighbouring island of Jerf Sgheïr. A group or groups of humans settled on the peninsula and exploited the Anadara to form the 4900 B.P. midden.

262. Shelter afforded by the spit to the east eventually culminated in it’s infilling, fed notably by alluvial sand deposits from the Oued ech Chibka. Between 4900 and 4600 years B.P., human groups established middens on beaches below Jerf Sgheïr. These eastern bay beaches were well protected and lay outside the zone of high storm waters.

273. A subsequent phase is evidenced by middens that testify to the continued silting up of the eastern bay. This phase is constrained by the 4435 B.P. Anadara shells.

284. Up to ca. 3200 years B.P., alluvial deposits accumulated and contributed to the formation of the first tombolo at Jerf el Oustani. At the end of this phase, the old estuarine bay was divided into two bays on either side of the tombolo.

295. The bar has been dated to 2900 years B.P. To the south and on the northern boundary of the tombolo of Jerf el Oustani, the bay was gradually filled in. This phase seems to have been rapid: to the north, the berms dated ca. 2700 years B.P. and advanced by about 1 km within 5 to 7 centuries (between 3200-3300 years BP and ca. 2600-2700 years BP). At the beginning of this phase, the last Anadara-collecting populations settled on the highest bars. The same climatic deterioration that led to their departure may also account for increased sedimentary inputs by aeolian processes (“Tafolian” according to Hébrard, 1978).

306. The final episode culminated in the currently prevalent geomorphological setting. It has not been dated, either archaeologically or radiometrically. It is nonetheless documented by abundant beach forms that mark the progradation of a second tombolo behind El Sass, before a gradual regularisation of the coastline to the north and south of this breakwater obstacle. A comparison of IGN aerial photographs from 1954 and satellite images taken during the 1990s indicates that these coastlines continue to evolve today. The beach has prograded by about 300 to 400 m along the cliff of Ras el Sass, whereas the western cliff of Jerf el Oustani, active in 1954, has become fossilised, separated from the sea by a beach more than 100 m wide (fig. 9).

Fig. 9 – Recent stages of the shaping of the shoreline. 1954: IGN photograph; 1990s: satellite image.

Fig. 9 – Étapes récentes de la régularisation du trait de côte. 1954: photo IGN; années 1990: image satellitaire.

31The sequence of deposits formed during the silting up of the estuarine bay attests to a dynamic system, the spatial and temporal evolution of which is governed by a balance between three allocyclic factors (Vail et al., 1977): variations in sea level, crustal deformation, and sediment budgets. The first of these factors is of general scope; the entire variation of sea level occurs at oceanic scale. The second involves substrate loading, in general in a remote past, whether positive or negative epirogenic movements or the coseismicity resulting from known tectonic features (Pirazzoli et al., 1994). Sediment compaction (subsidence) is difficult to quantify but can be apprehended by other methods (Pirazzoli, 1998). The third factor is more circumstantial, resulting from the interplay between climate and hydrology. In terms of frequency, sea-level variation comes into play at a medium temporal and low spatial frequencies, crustal deformation occurs at a low temporal and medium spatial frequencies, and parameters relating to sediment budgets at both high temporal and spatial frequencies. The first factor is often used to explain the architecture of late Holocene coastal deposits.

32In the Jerf el Oustani region, the issue is limited, in fact, to determining the relative weight between two factors: eustasy and sediment infilling. The area is situated on the West African passive margin and, although there are indicators of crustal mobility in the region, these are generally limited to subsidence in the region of the Senegal River delta (Monteillet, 1986). To explain it, Faure and Hebrard (1977) and Faure et al. (1980) also consider hydro-isostatic residues, the influence of which is favoured by the lower resistance of the crust at this level.

33Lithospheric stability otherwise prevails elsewhere (Einsele et al., 1974, 1977a and b; Amblard et al., 1990). Furthermore, accumulations of Eemian age near current sea level on the oyster rock (Ostraea stentina) of El Hadjra to the south of the Banc d’Arguin (‘Inchirian’ of Elouard, 1975), as well as the recent discovery of an oyster bed under the ‘Nouakchottian beach’ near the Ras Iwik close to present MSL confirm this hypothesis. Further to the south, the observations of the Cap des Biches (Diouf, 1989; Diouf et al., 1995), where the Eemian shoreline is encountered at a low altitude (~1 m) above sea level, show that this stability can be extrapolated to the entire Senegalo-Mauritanian sedimentary basin and at a temporal scale that straddles the Holocene.

34Under these conditions, the discussion is limited to determining which of these two factors, i.e. eustasy or sediment filling, played the most significant role. Faure and Elouard (1967) only considered the combined influences of eustatic and epeirogenic factors, and completely neglected the sedimentological parameters.

35First, it is noted that the sediment reservoir was considerable throughout this period. The creation and redistribution of sands can be considered from three perspectives. During the entire glacial phase, corresponding to dry periods (Sarnthein and Walger, 1974; Williams, 1975; Beaudet et al., 1976; Sarnthein, 1978; Stein et Sarnthein, 1983) abundant material was supplied by crystalline outcrops situated to the east. The voluminous ergs that resulted extended not only to the current coastline (‘Ogolian’; Michel, 1977) but also onto the exposed continental shelf, and in particular across the entire Banc d’Arguin and beyond. This material was subsequently reworked during the post-glacial transgression, and part of it contributed to the formation of successive beach ridges. The third point is undoubtedly the most important, because it is contemporary to all the deposits that led to the infilling of the estuarine bay. It resulted from alternating humid and arid phases during the course of which the previous sand deposits were reworked. These climatic phenomena led to the superposition of dune systems separated by complex surfaces of erosion or paraconformities, or even surfaces of non-deposition (Deynoux et al., 1991; Kocurek et al., 1991) corresponding to humid phases. The most important one took place between 10,000 and 3000 years B.P. and forms supersurface I at Akchar (Ould Ahmed Benan, 1991). During the arid phases, the dunes were remobilised on the vast system of Ogolian ergs, in particular during the Tafolian episode (Hébrard, 1973, 1978). Consequently, we have the transport agents (fluvial systems during humid phases, wind during the arid phases) and the abundant sand material that they remobilised throughout the period. This mechanism is still observed at present with the imposing lines of barkhans that carry the sands towards the SSW and discharge them in the sea, where they are reworked by the coastal drift. Since sea level reached its present position, the morphodynamic evolution has been controlled by swell waves, leading to the emplacement of the coastal features observed today.

36The question arises as to whether any positive and/or negative variations in sea level occurred during the silting up phase of the estuarine bay. Such variations have frequently been cited to explain the architecture of the deposits (Faure and Elouard, 1967; Einsele et al., 1974, 1977b; Monteillet et al., 1981; Médus, 1987; Barusseau et al., 1989; Deynoux et al., 1991; Vernet and Tous, 2004). The observations reported here do not seem to require any marked variation in sea level. Furthermore, such sea-level variations are not presently demonstrable from the available data. The arguments against any real sea-level variation effect on the geomorphic evolution deduced from the various datasets concern: (1) the altitude of the deposits, (2) the absence of erosion, and (3) a classic progradation pattern. The altitude of all the identified deposits (beaches or beach berms) is consistent with the current tidal range. It should also be borne in mind that the coastal sand prism is subjected to storms that raise the maximum tidal level. This means that deposits of up to + 2 m above MSL can be compatible with the present level in the Ras el Sass – Jerf el Oustani region. No erosion has been observed. In theory, this should have accompanied the hypothetical regressive movements. Finally, the infilling deposits show a classic progradation tendency, with the oldest deposits being furthest from the sea. Better chronological resolution would assist in quantifying the rate of coastal progradation. It does appear, however, that it was particularly rapid after 3000 years B.P. This rapidity could account for the good preservation of the berms to the west of the Jerf el Oustani tombolo.

37The morphodynamic study of the late Holocene evolution of Ras el Sass – Jerf el Oustani was conducted using a double archaeological and sedimentological approach. The archaeology yielded a robust chronological framework for the different Neolithic cultures. The shell middens built by these societies served both as chronological markers and as evidence of the position of successive palaeoshorelines. This geomorphological study completes our understanding of the area’s morphodynamic evolution. This comprises different phases, evolving from an open estuarine bay during the maximum marine ingression to a regularised coastline and silted up palaeobay at present.

38The geomorphology has essentially been driven by high sediment supply to the coastal zone (fluvio-aeolian sands) and the redistributing action of coastal processes.

39The sedimentary filling stages include the accretion of a coastal spit between the Tafaritian cliff at Îmgoutene towards the Isle of Jerf Sgheïr, then by the progradation of two tombolos formed in succession at Jerf el Oustani and at Ras el Sass. Between these two episodes, evidence of rapid infilling between 3000 and 2700 years B.P. is consistent with the last phase of human occupation in the region.

40In the absence of a significant tectonic component, relative sea-level changes during the past 5000 years do not account for the observed changes in the Ras el Sass – Jerf el Oustani area. It is possible that changes of limited (centimetric) scope could have occurred, but these did not reach 1 to 2 m in height. Conversely, the sedimentary forcing caused by (1) the abundance of sand resources throughout the period, (2) the existence of limited yet stable accommodation space and, (3) the continued presence of an active coastal dynamic, explain the pattern of coastal geomorphology elucidated in this study.